“Traffic Relief Plan,” Maryland

In February 2018, Maryland had a transit emergency. That month, Baltimore’s entire Metro SubwayLink system was shut down for a month after inspections revealed that the subway was becoming dangerous and needed emergency repairs. The closure immediately threw into disarray the commutes of 34,000 daily riders and shined a light on years of neglect of the system. Meanwhile, in the Washington, D.C., area, much of which is in Maryland, the Metrorail system has seen reliability suffer and experienced several high-profile safety incidents following years of deferred maintenance.

Status: Study and review

Originally reported cost: $9 Billion

Update from Highway Boondoggles 7: Maryland’s I-270 widening mired in controversy

Highway Boondoggles 4, in 2018, covered Maryland’s massive, $9 billion “Traffic Relief Plan,” which featured hundreds of lane-miles of highway widening, including on Interstate 270 northwest of Washington, D.C., and Interstate 495. The plan for I-270 has since faced intense criticism, been downsized, and become mired in legal battles.

The plan to widen I-270 was opposed by environmental groups and local officials, who argued the project wouldn’t achieve its goal of reducing congestion, but would increase air, water and climate pollution and encourage sprawl. Opponents also took issue with the planning and design process and the lack of consideration of alternative solutions. Partly in response to that opposition, state transportation officials cut back on their proposal in May 2021, shrinking the scope of the project. The changes neither satisfied environmental groups, who argued that the same problems existed in the newer plan, nor lawmakers, who argued that the Maryland Department of Transportation (MDOT) had failed to consider alternative approaches to funding and construction that could save taxpayer money. In June 2021, the regional Transportation Planning Board removed the project from its plan for air quality analysis, a requirement for federal approval.

Governor Larry Hogan quickly pushed the board to reconsider the plan. U.S. PIRG responded by noting the environmental destruction the project would entail and the analyses showing that tolls could be up to 200 times the national average and still not cover the cost of the project, forcing taxpayers to cover up to $1 billion in subsidies despite the governor’s claim that there would be no cost to the public. However, after threatening to cut over $1.2 billion in transportation funding for other projects around the state if the I-270 project were to be cancelled, and promising tens of millions of dollars in transit funding if it were approved, Governor Hogan was able to convince the board to reverse its decision and include I-270 in the air quality analysis plans.

In September 2021, MDOT released its supplemental draft environmental impact statement for the project, analyzing the potential damage to the surrounding natural spaces and communities and modeling potential benefits. That study found very few and relatively small congestion benefits for drivers using non-tolled lanes on the widened I-270, both in terms of average travel speed and time saved on delays, contradicting many of MDOT’s claims about the effects of the project. In fact, MDOT wrote that the claimed benefits of the project could not be achieved without significant additional work. Those additional projects were recommended for no action, and would need separate environmental study, analysis, public participation periods and agency review processes.

In early 2022, the I-270 project ran into further difficulty, this time legal. After MDOT selected a team led by two Australian companies to design, build and operate the new lanes on I-270, one of the other bidding teams filed an appeal claiming that the winning team had used unrealistically low construction costs that could lead to cost overruns and delays. MDOT twice rejected the appeal, after which the losing bidder took the issue to court where, in February 2022, a judge ruled that MDOT had to consider the appeal. The judge expressed incredulity that the agency was claiming it could ignore the financial feasibility of the proposals because an appeal was filed late. The winning team may also have excluded the costs of permits, fees, payroll and insurance, according to Montgomery Circuit Court Judge John M. Maloney, assigned to rule in the case. Though spokespeople for the winning bidder said the timeline is not yet impacted by the ruling, other experts and observers believe the decision will delay contract finalization until early 2023, after a new governor has taken office.

The project’s federally required Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS), published in June 2022, claimed that design changes aimed at mitigating the environmental damage caused by the project would lead to less environmental harm than previously believed. Whether or not this claim is accurate, the environmental impacts of expansion far outweigh any benefits. For one, MDOT itself concedes that the plans will not solve congestion during peak commute times on the Beltway’s inner loop and on northbound I-270 due to the continued existence of key bottlenecks. The FEIS findings will be submitted to the FHWA for approval, necessary for the project to receive federal funding. They will also form the basis of the lawsuits likely to be filed against MDOT on environmental grounds over the next few months – lawsuits that will ensure the plans remain mired in legal battles and further stall construction.

Original story from Highway Boondoggles 4, 2018:

In February 2018, Maryland had a transit emergency. That month, Baltimore’s entire Metro SubwayLink system was shut down for a month after inspections revealed that the subway was becoming dangerous and needed emergency repairs. The closure immediately threw into disarray the commutes of 34,000 daily riders and shined a light on years of neglect of the system. Meanwhile, in the Washington, D.C., area, much of which is in Maryland, the Metrorail system has seen reliability suffer and experienced several high-profile safety incidents following years of deferred maintenance.

Maryland recently agreed to cover its share of a $500 million annual funding plan for Metro with Virginia and the District of Columbia, a first step in restoring the system to health. But the investment in Metro pales in comparison to a massive highway expansion project that would likely put more Marylanders on the road.

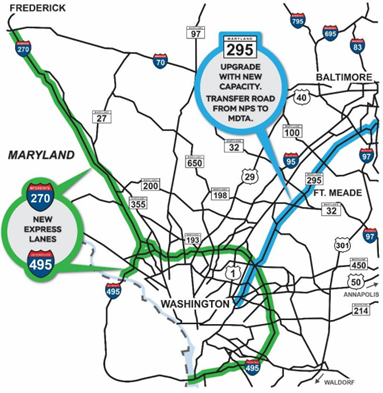

The proposed projects would be some of the biggest and most expensive highway expansion projects in the country. In total, the proposed “Traffic Relief Plan” would cost $9 billion: $7.6 billion to add four new lanes to I-495 and I-270, and $1.4 billion to add four lanes to MD-295, the Baltimore-Washington Parkway.

Maryland’s “Traffic Relief Plan” would entail adding new lanes along more than 100 miles of highway.

The three highways planned for expansion all cover important transportation routes in the Baltimore-D.C. area: I-495 encircles Washington, D.C., I-270 connects D.C. with Frederick, a major suburb northwest of the city, and MD-295 connects D.C. with Baltimore. Each route suffers from hours of congestion each weekday and is a source of pain for area commuters.

However, expanding Maryland’s already substantial highway capacity would likely bring minimal relief for those commuters. I-270 and I-495 are already eight lanes across, with miles of additional auxiliary lanes; for much of its route, MD-295 runs parallel to Interstate 95, which is also eight lanes across. As described above (“Highway Expansion Doesn’t Solve Congestion,” page XXX), highway expansions rarely reduce congestion because they result in more overall driving. Meanwhile, the plan would have large costs for the state of Maryland – for neighborhoods along the route, for Maryland taxpayers, and for Maryland’s transportation future.

Highway expansions along the proposed routes would likely require damaging existing neighborhoods. The Traffic Relief Plan Request for Information notes that along I-495, “[r]esidential and commercial development is located close to the right-of-way line,” and indicates that the project will require right-of-way property acquisitions. One response from an infrastructure investment company notes that “[m]ost of the corridor is built along dense residential, commercial and office areas.” I-270 and MD-295 also travel through stretches of dense development in the areas closest to Frederick, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C. Widening MD-295, which is a historic parkway currently maintained by the National Park Service, would also likely require diminishing that road’s scenic value.

I-270, MD-95, and I-495 (shown above) travel through dense residential and commercial areas, and their widening will likely require relocating homes and businesses. Image: ©2018 Google

The project also would cost Marylanders money – for new tolls, but also likely from state funds. The plan envisions that I-495 and I-270 would be built through a public-private partnership (PPP), under which a private company or companies would build the highways and then collect tolls for access to new express lanes, in a contract lasting a to-be-determined number of years. The MD-295 lane additions would be toll roads built by the Maryland Transportation Authority (MDTA).

Governor Larry Hogan has promoted the potential PPPs as a good deal for taxpayers, saying “[i]t won’t cost us tax dollars.” Yet this is misleading. The state’s own documents confirm that federal funds and loans will be sought for the project. And similar projects around the country have typically not been able to raise enough toll revenue to cover their costs. For example, tolls have not come close to covering the construction costs of additional lanes built for I-95 north of Baltimore.

One response to the project’s Request for Information notes that “toll revenues may not be sufficient to cover the entire costs of the Project,” and suggests that “MDOT might consider a ‘hybrid’ toll revenue and availability payment approach, or may choose to supplement toll revenue by contributing some amount of public subsidy as milestone or completion payments during/at the end of construction.” (For more on how PPP projects can affect state finances, see page X.)

Governor Hogan has also demonstrated his willingness to reduce tolls, regardless of the cost to the state, as when he reduced tolls at roads and bridges across Maryland in 2016. Future politicians may do the same, and the result may be the need for state payments to support the new highways.

Any new debt created by the project would add to Maryland’s already quickly-growing highway debt. At the end of 2015, Maryland owed $5.2 billion in state highway bonds, 5 times more than it did at the end of 2000, not adjusted for inflation. And in 2014, the state spent $492 million servicing highway debt, three times as much as it did in 2000.

New costs to Marylanders for building highways will make it more difficult to pay for other pressing transportation needs, including:

- Fixing and improving the Baltimore Metro.

- Funding the MARC commuter rail, which has had to rely on stopgap funding measures to remain in service.

- Building more and better urban transit. This includes the proposed Red Line light rail extension, which would have connected Baltimore neighborhoods, improving transportation options in the city while helping Maryland residents live in the city and avoiding sprawl. In 2015, Governor Hogan cancelled the extension.

- Repairing roads and bridges. More than half of Maryland roads are in poor or mediocre condition, and 27 percent of bridges are structurally deficient or functionally obsolete.

Topics

Find Out More

Clean cooking tips from Sen. Heinrich

Who are the top climate polluters in the country?