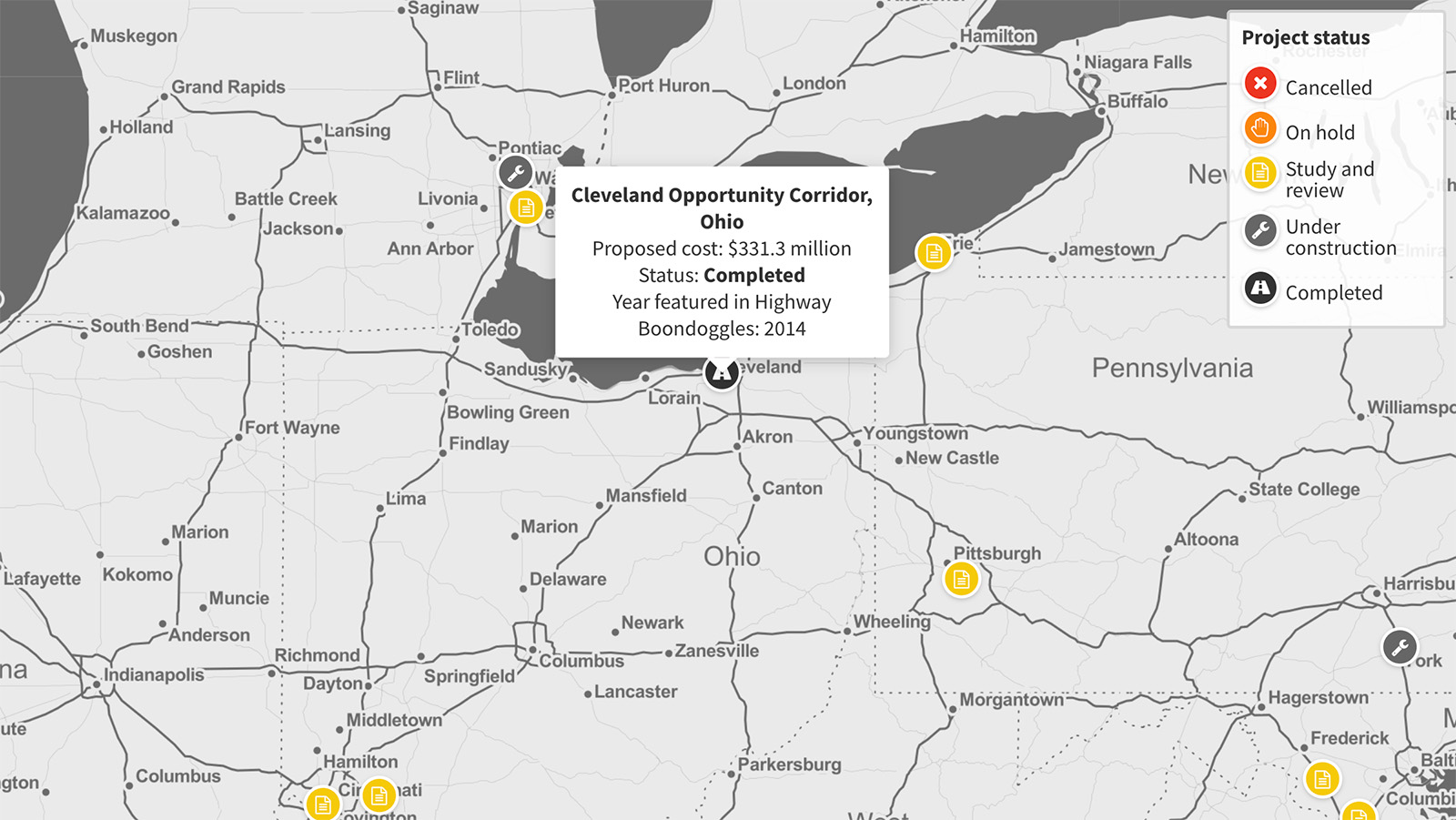

Cleveland Opportunity Corridor, Ohio

The Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) is promoting a $331 million, three-mile, five-lane road construction project starting at I-490’s terminus south of the city’s downtown and running northeast to the University Circle neighborhood. But it’s hard to see what need it would be meeting. The number of miles driven in and around Cleveland has been stagnant for more than a decade. And though project proponents have tried to package the project as an “opportunity corridor” that would help the disadvantaged neighborhoods the road would traverse, the communities that would supposedly benefit have other priorities. Part of the neighborhood would also have to be destroyed to make room for the road.

Status: Completed

Originally reported cost: $331 million

Update from Highway Boondoggles 5, 2019: Boondoggles put Ohio in a budget hole

Previous Highway Boondoggles reports covered two Ohio projects: the Portsmouth Bypass, a $429 million project that we noted was “in an area where driving has declined and existing roads desperately need funding for repairs,” and the Cleveland Opportunity Corridor, a $331 million project that critics noted was “unnecessary since there are several routes in the area that connect the two points already.” At the same time, as we wrote in 2015 with regards to the Portsmouth Bypass, its costs would “encumber future budgets, eating up money that could be used in the future for education, health care and other necessities.”

Despite tight funds and questionable rationales, those projects moved forward. Today, after years of reckless highway spending, Ohio is struggling to fund its transportation budget. In 2018 the Columbus Dispatch wrote that “the incoming DeWine administration will start off the new year staring down a huge transportation-budget problem: The state has run out of money for major new road-construction projects.” And a 2017 spending analysis found that Ohio’s annual spending on public transit was falling more than $650 million short of what was needed to meet market demand, noting that the “Ohio Department of Transportation itself has found the state’s public transit network fails to meet market demand by 37.5 million rides.”

In recognition of the budget hole, Ohio was able to muster the political will to raise gas and diesel taxes, which will raise an estimated $865 million in revenue per year. Yet even with the new revenue, Ohio still faces big transportation budget problems – problems that will only worsen if the Ohio Department of Transportation uses the new revenue for yet more highway expansion projects, as the agency has indicated it intends to.

As news site WCPO Cincinnati asked, “will Ohio keep widening highways when it can’t afford to maintain what it has already built?” And while the state’s long underfunded transit systems will receive some money under new legislation, fuel tax revenue in Ohio can only be spent on roads and bridges. To fix its budget and achieve a better transportation future, Ohio will have to let go of wasteful and unnecessary highway projects.

Update from Highway Boondoggles 4, 2018:

The Cleveland Opportunity Corridor is a $331 million, five-lane, three-mile planned boulevard that would connect I-490’s south end to the northeastern University Circle neighborhood. Critics had previously pointed out that the road is unnecessary since there are several routes in the area that connect the two points already. Work on the road is underway, although construction on the largest phase of the project was delayed by a lawsuit.

Original story from Highway Boondoggles, 2014:

The Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) is promoting a $331 million, three-mile, five-lane road construction project starting at I-490’s terminus south of the city’s downtown and running northeast to the University Circle neighborhood. But it’s hard to see what need it would be meeting. The number of miles driven in and around Cleveland has been stagnant for more than a decade. And though project proponents have tried to package the project as an “opportunity corridor” that would help the disadvantaged neighborhoods the road would traverse, the communities that would supposedly benefit have other priorities. Part of the neighborhood would also have to be destroyed to make room for the road.

Expanding road capacity is a questionable investment given recent travel trends in the Cleveland area. While ridership on the regional transit authority has been increasing,149 vehicle-miles traveled (VMT) in Cuyahoga County rose an anemic 0.3 percent from 2000 to 2013, an annual average of 0.02 percent. In the five counties making up the Cleveland-Elyria Metropolitan Statistical Area, VMT climbed just 1.9 percent from 2000 to 2013, an annual average increase of 0.14 percent.

Residents of this troubled Cleveland neighborhood that would have to be destroyed to make room for a large road have not had their voices heard or their needs met by Ohio Department of Transportation officials. Credit: Bob Perkoski

Critics of the project point out that the $100 million per mile set aside for constructing the new road could instead provide more than enough money to fix all the roads in Cleveland that need repaving and repair. (ODOT declared that it has a “fix-it-first” policy that is supposed to prioritize repair of existing roads over construction of new highways, but the agency lacks policies to ensure the principle is actually followed.) The $331 million price tag is also larger than the annual budget of the city’s public transit system. That system already does not adequately serve the existing neighborhoods, and in fact is slated to serve them worse with the expected closing of a key rail rapid-transit stop.

The positive economic effects that project backers claim will flow to the neighborhoods traversed by the Opportunity Corridor are vague at best. And local developers are skeptical that any benefit of the road would arrive without significant additional public investment. The project design documents acknowledge that some impacts on the local neighborhood will be “disproportionately high and adverse,” including relocating 76 households and 16 businesses, as well as a church, and turning nine roads that currently connect with other streets into dead ends.

In an effort to mitigate those impacts, and provide options for local residents without cars, ODOT proposes to build two pedestrian/bicycle bridges over the new road, improve bus shelters along the new road, and “create a new entrance to the St. Hyacinth neighborhood by constructing enhancements . . . [that] will include street trees and sidewalk and pavement repairs or improvements.” Community residents, however, say most of that work wouldn’t be needed if not for the new road itself, and in any case it’s not enough to boost local economic development measurably. And those are just the community members who have gotten involved in a process that has taken significant criticism for leaving out the voices of local residents.

A highway construction project makes little sense as an economic development tool for the neighborhood, where as many as 40 percent of residents do not drive at all. It also goes against the expressed desires of residents around the region, who are calling for increased investments in public transportation and in the development of communities that are less dependent on cars.

A 2012 survey by the Natural Resources Defense Council found that “a combined 68 percent of Cuyahoga County respondents say improving public transportation (35 percent) and developing communities where people don’t have to drive as much (33 percent) are the best ‘long term solutions to reducing traffic’ in their area—rather than other options like building roads (21 percent).”

Topics

Find Out More

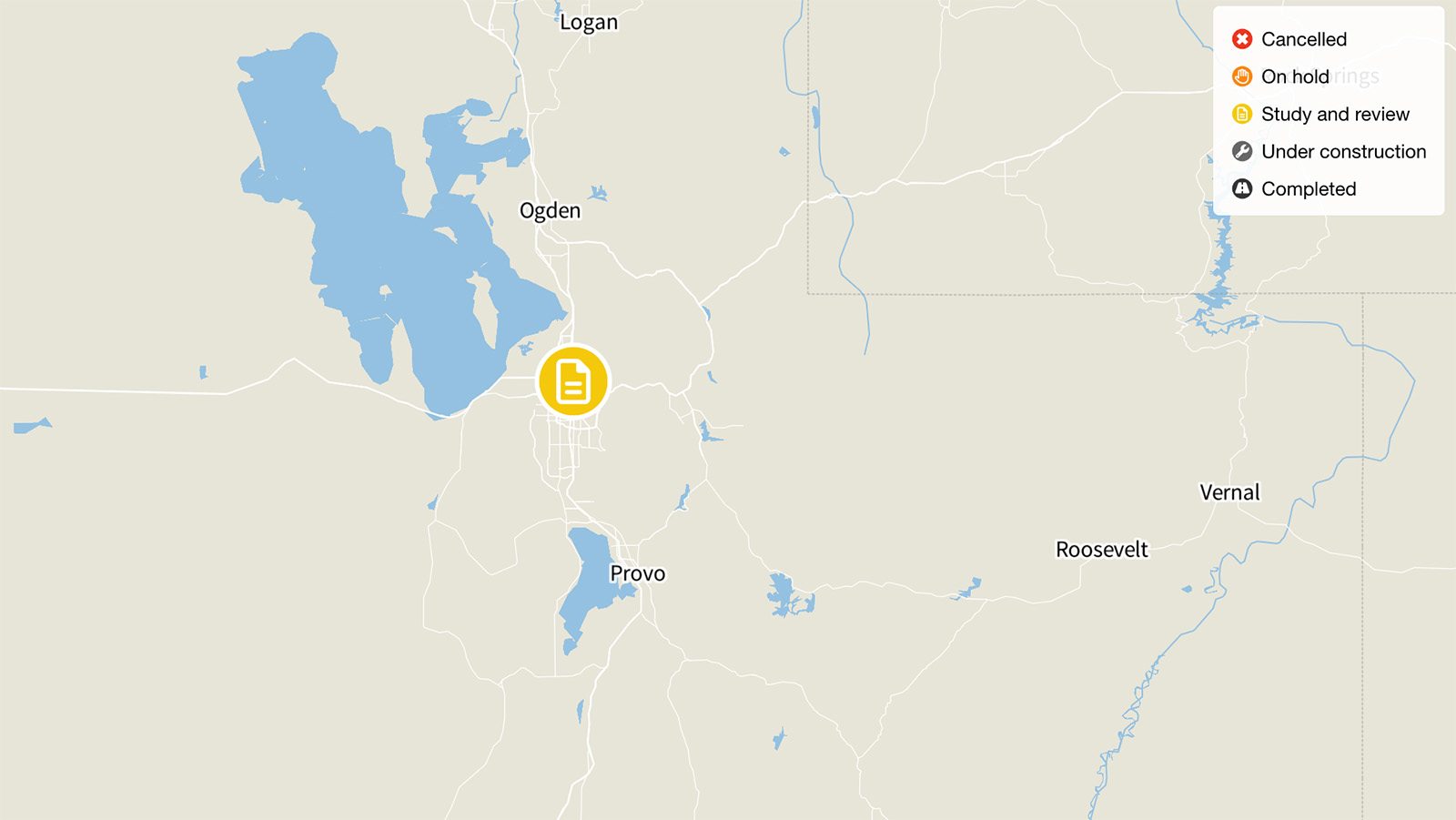

I-15 Expansion, Salt Lake City

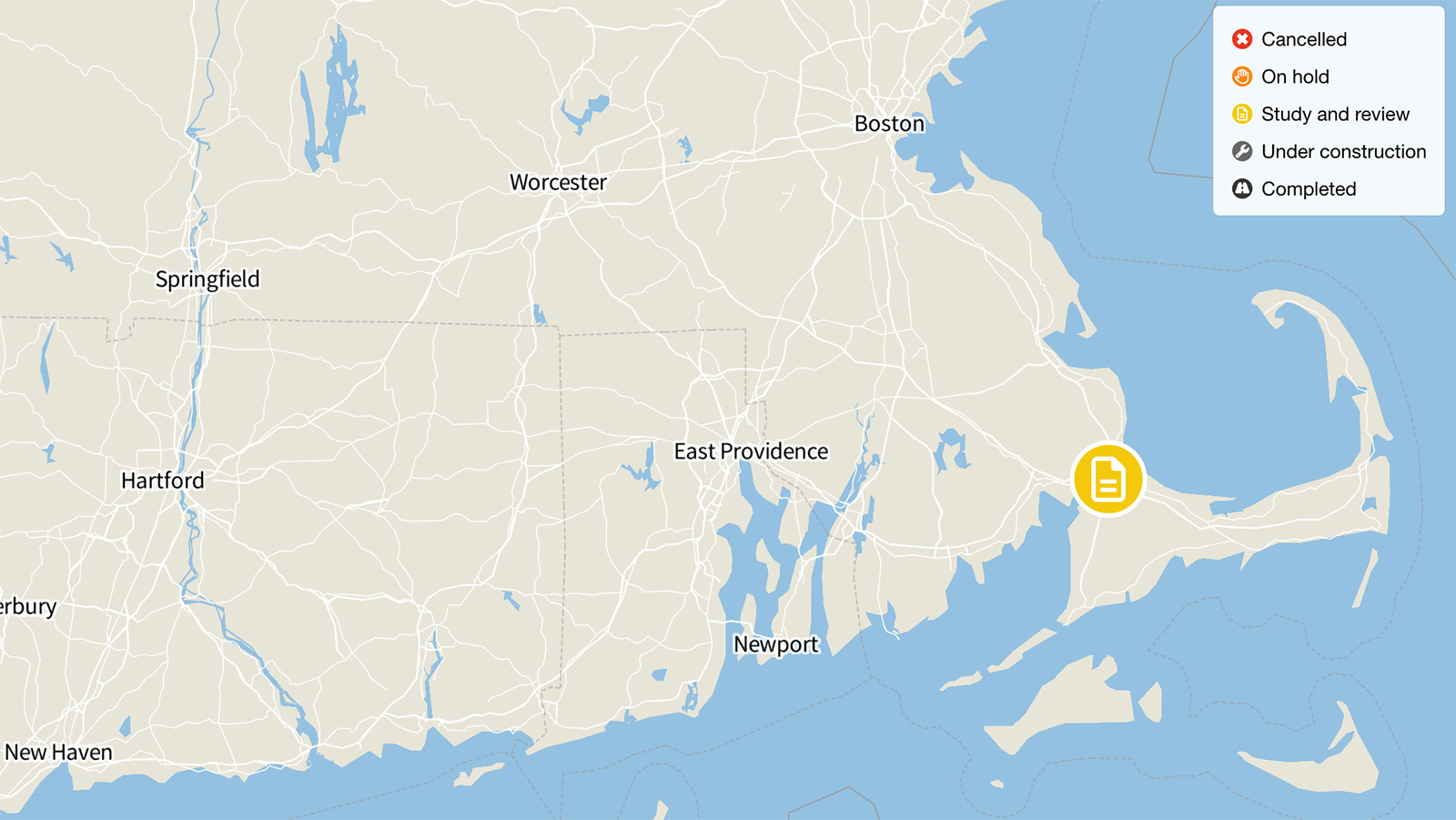

The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, New York