Highway Boondoggles 5

Big Projects. Bigger Price Tags. Limited Benefits

Highway Boondoggles 5 finds nine new budget-eating highway projects slated to cost a total of $25 billion that will harm communities and the environment, while likely failing to achieve meaningful transportation goals

Downloads

U.S. PIRG Education Fund

America’s aging roads and bridges need fixing. Our car-dependent transportation system is dangerous, harms our communities, and is the nation’s leading source of global warming pollution. And more than ever before, it is clear that America needs to invest in giving people healthier, more sustainable transportation options.

Yet year after year, state and local governments propose billions of dollars’ worth of new and expanded highways that often do little to reduce congestion or address real transportation challenges, while diverting scarce funding from infrastructure repairs and key transportation priorities. Highway Boondoggles 5 finds nine new budget-eating highway projects slated to cost a total of $25 billion that will harm communities and the environment, while likely failing to achieve meaningful transportation goals.

Highway expansion costs transportation agencies billions of dollars, driving them further into debt, while failing to address our long-term transportation challenges.

Highway expansions are expensive and saddle states with debt.

- In 2012, the latest year for which data is available, federal, state and local governments spent $27.2 billion on highway expansion projects – sucking money away from road repair, transit, and other local needs.

- From 2008 to 2015, the highway debt of state transportation agencies nearly doubled, from $111 billion to $217 billion.[i]

- New roadway is expensive to maintain, and represents a lasting financial burden. The average lane mile costs $24,000 per year to keep in a state of good repair.[ii]

Highway expansion doesn’t solve congestion.

- Expanding a highway sets off a chain reaction of societal decisions that ultimately lead the highway to become congested again – often in only a short time. Since 1980, the nation has added more than 800,000 lane-miles of highway – paving more than 1,500 square miles, an area larger than the state of Rhode Island – and yet congestion today is worse than it was in the early 1980s.[iii]

Highway expansion damages the environment and our communities.

- Highway expansion fuels additional driving that contributes to climate change. In 2017, transportation was the nation’s number one source of global warming pollution.[iv]

- Highway expansion can also cause irreparable harm to communities – forcing the relocation of homes and businesses, widening “dead zones” alongside highways, severing street connections for pedestrians and cars, and reducing the city’s base of taxable property.

A look back at five projects from past reports shows the consequences of following through with boondoggle projects and the benefits of rejecting them.

- In May 2018, local groups stopped a plan to add toll lanes along I-275 through the neighborhood of Tampa Heights, in Tampa Bay, Florida. Now, the community is thriving, with new restaurants and businesses, and even efforts to reduce traffic capacity on local roads to improve walking and biking.

- After years of devoting scarce transportation dollars to unnecessary road expansion projects, including the Portsmouth Bypass and Cleveland Opportunity Corridor covered in past reports, Ohio found itself in a deep budget hole. Now, even with new fees and taxes in place, the state is falling billions of dollars short of being able to fix aging roads and adequately fund transit.

- For years, Wisconsin’s reckless highway spending strained the state budget. But in 2018, then-governor Scott Walker made an about-face, cancelling one “boondoggle” project, and announcing his support for a fix-it-first spending strategy – and dedicating modest new funding for transit and local infrastructure maintenance.

- The six-lane Dallas Trinity Parkway would have run alongside the city’s most prominent natural feature, the Trinity River. But local opposition eventually stopped the project – and now Dallas is planning new parks and open spaces for the river corridor, and creating the promise of a greener, healthier and more enjoyable city.

- Prior to the closure of Seattle’s old Alaskan Way Viaduct highway, critics suggested that the three-week wait until the opening of an expensive new highway would see horrible commutes and endless traffic jams. Instead, observers were surprised to see most of the traffic simply melt away – a real-life lesson that many urban highways are more disposable than they seem.

States continue to spend billions of dollars on new or expanded highways that fail to address real problems with our transportation system and will create new problems for our communities and the environment. Questionable projects poised to absorb billions of scarce transportation dollars include:

- Complete 540; North Carolina; $2.2 billion: North Carolina’s plan to complete the southern half of a loop highway around Raleigh would generate sprawl while destroying wetlands and threatening endangered wildlife.

- North Houston Highway Improvement Project; Texas; $7+ billion: A massive highway project in Houston would harm communities, displace residents and destroy businesses, while sucking billions of dollars away from important transportation priorities.

- High Desert Freeway; California; $8 billion: In stark contrast to California’s efforts to reduce state global warming emissions, L.A. County’s first new highway in 25 years would lead to more driving and more pollution, along with sprawling desert development.

- I-75 Widening; Michigan; $1 billion: In a region that has experienced little population growth over the last 20 years, a needless widening project would exacerbate sprawl and harm the communities through which it runs.

- Tri-State Tollway Widening; Illinois; $4 billion: The Tri-State Tollway outside Chicago is testament to the fact that you can’t build your way out of congestion. It has been widened twice, and still suffers from heavy traffic. Nevertheless, the Illinois Tollway is still moving forward with a $4 billion expansion project.

- “Connecting Miami” Widening Project; Florida; $802 million: Florida is widening I-395 and SR836 in Miami, highways that have long divided communities. Local groups have identified far more promising ways to benefit the neighborhood, including improving transit or even converting I-395 to a street-level boulevard.

- I-83 Widening; Pennsylvania; $300 million: A widening project in southern Pennsylvania is being touted as a way to improve traffic flow, but project documents reveal that traffic congestion is not a problem to begin with, and that resources would be far better spent on operational improvements to reduce crashes and improve accident response.

- I-5 Rose Quarter Widening; Oregon; $450 million: In Portland, a city that has taken great strides toward more sustainable transportation, an expensive highway project would constitute a step backward to the car-dependent policies of the past. It would also likely fail to meaningfully improve safety compared with other investment strategies.

- Interstate 81 Widening; Virginia; $2.2 billion: Virginia argues an expensive widening project is necessary for safety, yet recently increased speed limits along the route – a move that likely made the road more dangerous. Rather than widening, solely implementing the operational improvements included in the current plan would be a far cheaper and more effective way to improve safety.

Federal, state and local governments should stop or downsize unnecessary or low-priority highway projects. Specifically, policy-makers should:

- Invest in transportation solutions that reduce the need for costly and disruptive highway expansion projects. Investments in public transportation, changes in land-use policy, road pricing measures, and technological measures that help drivers avoid peak-time traffic, for example, can often address congestion more cheaply and effectively than highway expansion.

- Adopt fix-it–first policies that reorient transportation funding away from newer and wider highways and toward repair of existing roads, bridges and transit systems.

- Use the latest transportation data and require full cost-benefit comparisons, including future maintenance needs, to evaluate all proposed new and expanded highways. This includes projects proposed as public-private partnerships.

- Give priority funding to transportation projects that reduce growth in vehicle miles traveled, to account for the public health, environmental and climate benefits resulting from reduced driving.

- Invest in research and data collection to better track and react to ongoing shifts in how people travel.

[i] U.S. Department of Transportation, Highway Statistics (2008 and 2015), available at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/statistics/2008/sb2.cfm and https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/statistics/2015/sb2.cfm.

[ii] Rayla Bellis et al., Transportation for America, Repair Priorities 2019, May 2019.

[iii] 1,500 square miles based on expansion of public road lane miles from: U.S. Department of Transportation, Highway Statistics 2015, Table HM-260, December 2016, and a conservative assumption of 10-foot wide traffic lanes.

[iv] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks, 1990 – 2017, 11 April 2019.

[v] U.S. Federal Highway Administration, Highway Statistics Series Table SB-2 (for years 2000-2016), available at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/statistics.cfm.

Correction (6/21/19): The impact of L.A. County’s High Desert Corridor on vehicle miles traveled has been corrected to reflect uncertainty regarding state projections.

Topics

Find Out More

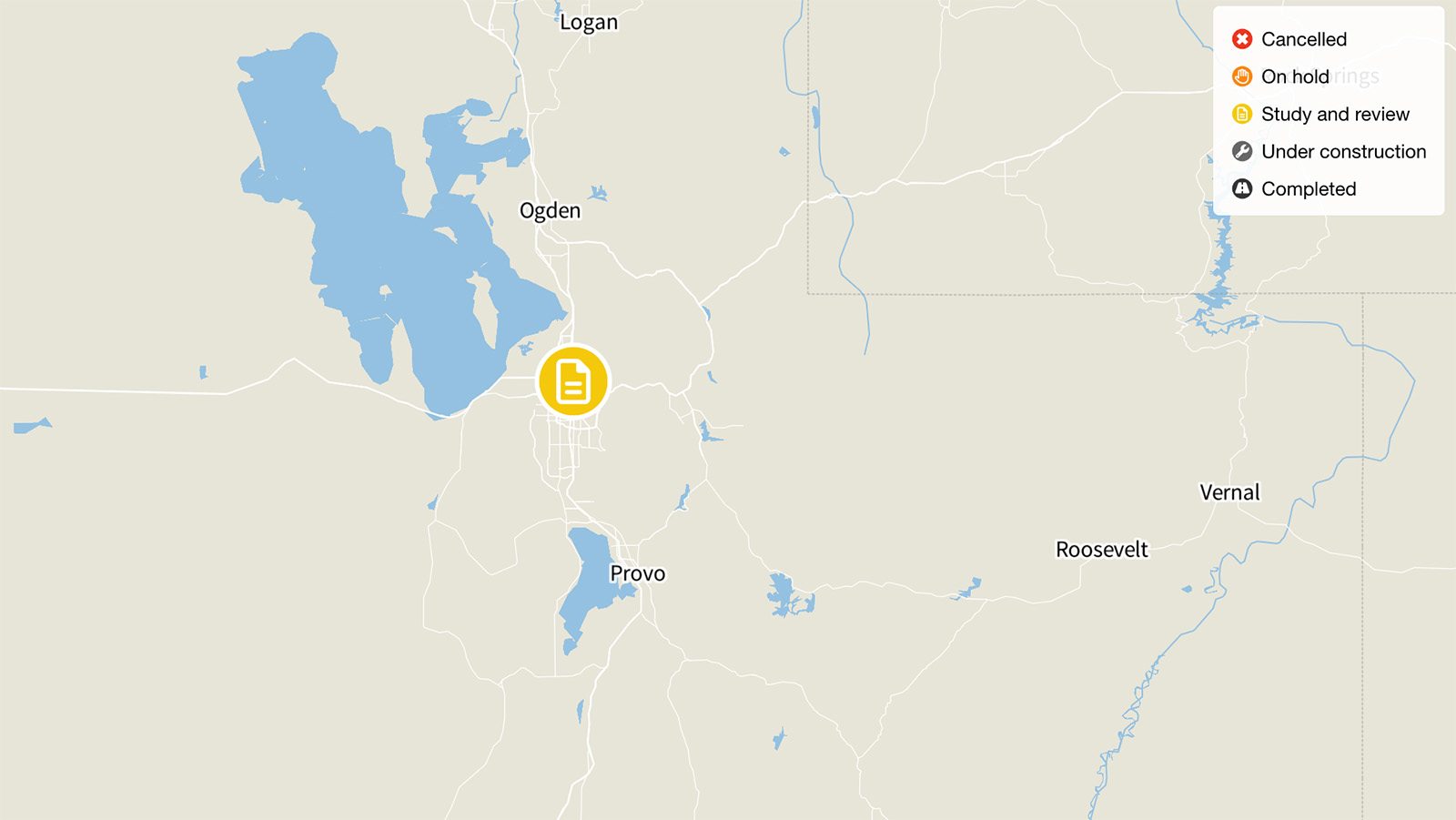

I-15 Expansion, Salt Lake City

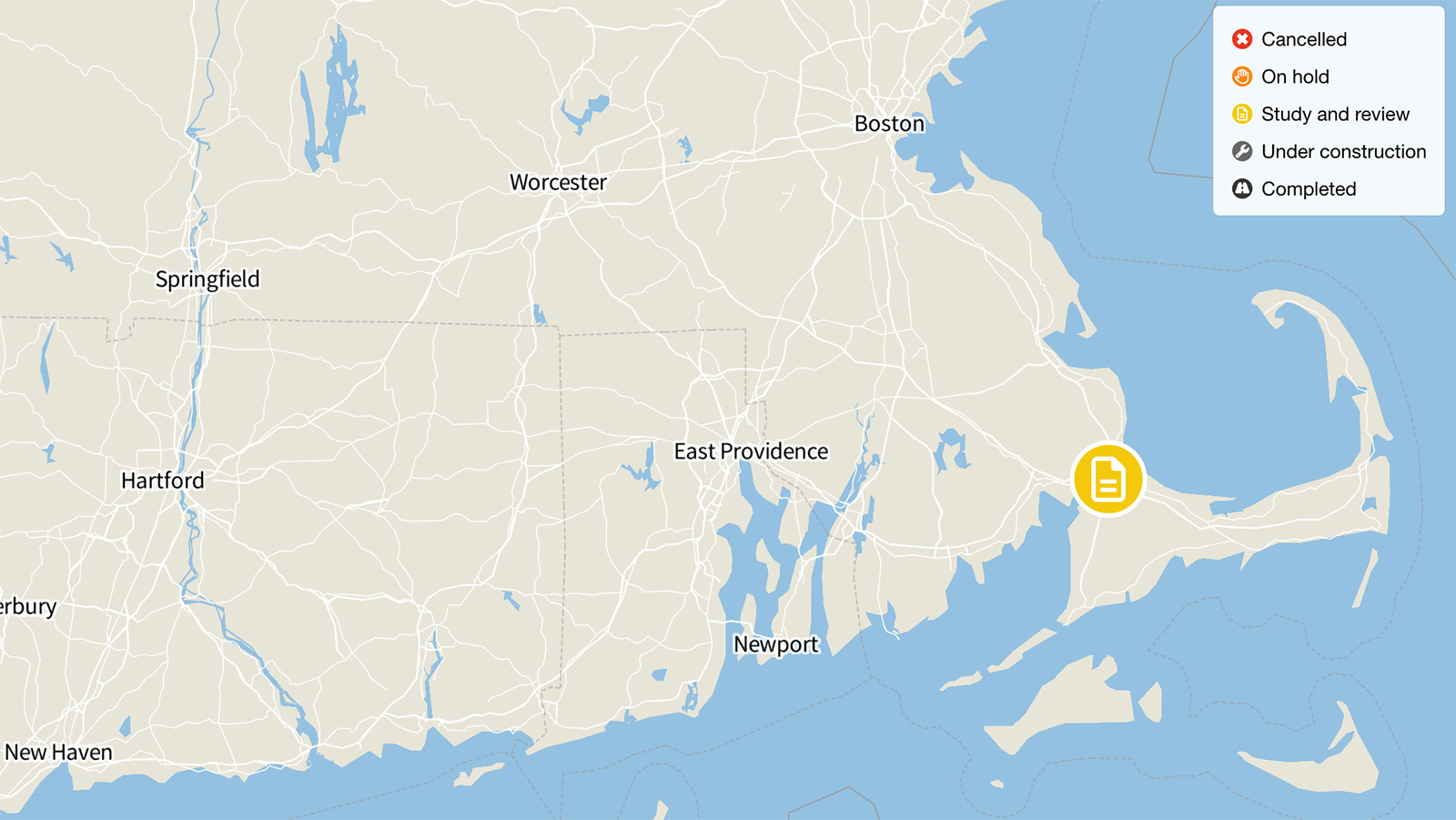

The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, New York